Games ay? They’re pretty cool.

From games that challenge your perceptions to games that purely tickle your funny bone, the variety and splendour of the current games scene is unique and everyone understands what it is they’re making.

But then virtual reality (VR) came along and ruined everything.

Seriously, game developers thought they had all their beans in the can; racing games, adventure games, puzzle games, strategy and action, all worked out and working fine on consoles and computers. The thing about game developers is that we like to think we know what we’re doing and when a new technology rears its head we rush blindly towards it with our irrepressible ‘can do’ attitude, tackle it to the ground and yell, ‘I’ve got it!’ Yes, yes you have. But here’s the thing about new gaming technology for game devs – the rules change every time, new technologies come with their own creative logic, and nowhere is this clearer than with the emergence of VR.

Let’s tackle the big one: movement (or: locomotion) in VR. Movement is something game devs take for granted. Controllers and mouse & keyboard have become staples of gaming input for many years now; they perfectly allow for complete three-dimensional movement. Remember the joystick? There’s a reason the classic joystick is no longer used in gaming, it didn’t allow for the movement required to engage with more technologically advanced games. Joysticks: great for Pac-Man, bad for Counter Strike. So controllers and mouse & keyboard won the battle and entered an awkward détente with one another. Finally, gaming had its input systems locked down; players implicitly understand them and developers can base their designs around them.

But then VR.

‘It’ll be easy! We’ve mastered first-person movement. Of course it’ll work in VR!’ But then everyone starts feeling sick and people don’t know what to play in VR anymore. So what are we developers to do? There is a disconnect in VR between the immersion of the experience and the static nature of the player. From my understanding the science is pretty simple: the player’s brain thinks it’s moving whilst not physically moving, the brain gets angry and makes the attached human queasy as punishment for confusing it so.

One of the more widely accepted techniques is ‘Teleporting’ and has been demonstrated in both Epic’s Bullet Train demo and through Cloudhead Games’ ‘Blink’ technology. As the name suggests, teleporting literally moves the player to a new position within the environment as opposed to simulating walking/running to the new position. The logic being that the player feels the environment move around them rather than they are moving within the environment, thus reducing conflict within the player’s brain.

There has been concern that the ‘snap’ movement of teleporting can be disorientating to players, as such it has been suggested using transitional effects such as fading to soften the jerk into position. The Cloudhead Games team have also extended their Blink tech into something they’re calling ‘Volume Blink’ in which the player selects where they wish to teleport to and the position they will be facing when they ‘land’. By doing so they hope to provide players with a greater sense of control (and mental preparation) over their movements within VR.

Cockpits. More than being a word that makes me titter like a hyena, cockpits also act as a form of movement in VR experiences. In one sense the term is quite literal: the player is placed in the seat of an aircraft, mech or car from which they control and experience the game. In another sense it can be quite figurative; the practice often refers to the use of static objects locked around the player within their peripheral vision. These permanently static reference points limit the player’s field of view by giving them an environment within an environment for the brain to focus on, thus reducing the overstimulation that occurs from a massive field of view. Have you heard of people feeling dizzy when presented with a scene of absolute nothing? The principle at play here is quite relevant.

Without focus points within the environment the brain has to over-process in an attempt to position itself following any form of movement, thus causing discomfort and sickness. Games such as CCP’s Eve Valkyrie have put the cockpit to good use – though they have the advantage of narrative context to allow for the player to be kept in a cockpit – but, as mentioned earlier, the term ‘cockpit’ can be more figurative. Researchers from Purdue University, investigating simulation sickness – which bears many similarities to motion sickness – have found that placing a virtual nose in the low-centre of the player’s point of view can reduce sickness by 13%. While these results are nowhere near conclusive they do suggest the effect having a fixed focus point could have on the design of a VR experience.

An extension of the cockpit idea is to contain the player’s virtual environment to a 1:1 representation of the room they are physically in. By doing so the brain already has a physical sense of place in the virtual environment and is prepared for the possible movements of the player within its virtual equivalent. Now this isn’t to say that the virtual room has to be bland and boring like the real room, far from it, it can be a room in the sky, deepest space or a world made of jam but because the imprint in the mind of the player matches the virtual space there is less confusion when movement occurs. This design approach has been shown to work effectively in games such as Smash Hit Plunder and in Valve’s VR experience, Aperture Robot Repair. Not only does Valve’s experience take place in a contained space, allowing the player just enough room to move for the sake of freedom but not far enough to start confusing their bodies, but the HTC Vive headset (co-created by Valve) uses a chaperone system to map out the player’s physical game space and highlight this within the VR experience; ensuring their two worlds remain in-sync.

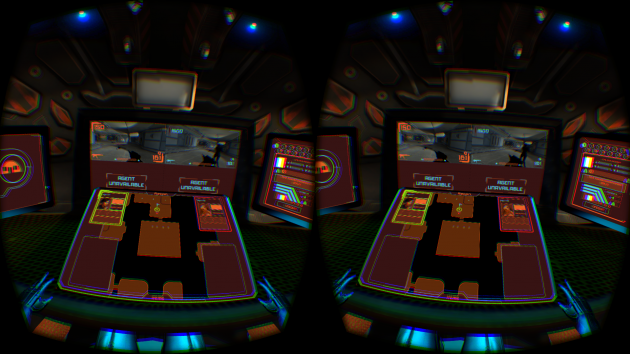

The use of ‘tunneling’, however, flies in the face of keeping things in-sync. A very recent experiment from Brantlew, tunnelling allows for traditional first-person perspective movement in VR. But how does it achieve this? When a player attempts to move, only the centre of their vision displays motion within the game space whilst the periphery of their vision remains static. This creates a tunnel effect, or a picture-in-picture effect, focusing the player’s eyes to the centre of their viewpoint rather than the wider field of view. When the player stops moving the two elements of their visions – the static periphery and the moving centre – seamlessly sync back into one image. In some ways it is akin to momentarily viewing a screen within the VR world and then having the screen blend with the player’s own vision, and best mirrors the sensations of playing a game on a television set.

Laying somewhere between tunneling and teleporting is a technique called ‘ghosting’ developed by Convrge. The principle of ghosting is to create a ghost image of the player that moves on their behalf within the virtual environment. Once the ghost, under the control of the player, reaches its desired location the player transitions to the new position. It seems that one of the trends of movement in VR is to not let the player move at all.

But why does the experience have to be from a first-person perspective? Insomniac are keen to show that third-person gaming works in VR with their ‘VR adventure’, Edge of Nowhere. Mike Bithell recently announced his PlayStation hit, Volume, is going to be playable in VR from a third-person perspective, with the player able to walk around a level to formulate their plans of attack. Whilst infinitely reducing the stress of motion sickness or any other motion qualms, one argument against third person VR gaming comes from the thematic concept of VR: it’s about being in the experience and viewing the experience from a omnipotent perspective might ultimately break this immersion. Perhaps a combination of first-person existence within the experience and switching to a third-person perspective for movement is a suitable compromise?

Virtual reality is a new technology for game developers. New things require new ways of thinking and new rules and a whole new gameplay language! But that’s the great thing about being a game dev at the dawn of something new and exciting: play, experimentation and learning. No one of the locomotion techniques above, or the many that’ll surely rise and fall in the future, might become the ‘defacto’ movement system for VR. They all have their positive potentials and negative implications but the most important thing to remember is that with each failed experiment game devs and the VR community learn something more and take another step forward.

We’ve been here before with mobile gaming, we assumed virtual D-pads *spits* would work for everything and we were wrong because a new technology needs new ideas, not old ones. Through play and research we turned mobile into a bona fide gaming platform and guess what? VR is next.

By Opposable Writer Designer-Producer Daniel Hunter-Dowsing and Senior Developer Lukas Roper.