You walk through a field of crisp, white snow. The sky a fresh blue, snowflakes hang in the air like fireflies. Ice floats in shades of teal on the black water of a lake. Penguins waddle past, you scoop up a handful of fluffy snow, pack it into shape before playfully throwing it towards them. You hear something on the air – the whimsical lyrics of Paul Simon.

Sounds like the greatest dream ever, right? Well guess again. What you have just experienced is SnowWorld, a ‘pain distraction’ virtual reality (VR) project created by the University of Washington’s own HITLab.

Researchers at University of Washington, working with burn victims, found that pain experienced during wound care – bandage changing, cleaning etc – registered as strongly as the original burn experience. Pain reducing drugs such as morphine, whilst effective during rest states, were found to be highly ineffective during wound care.

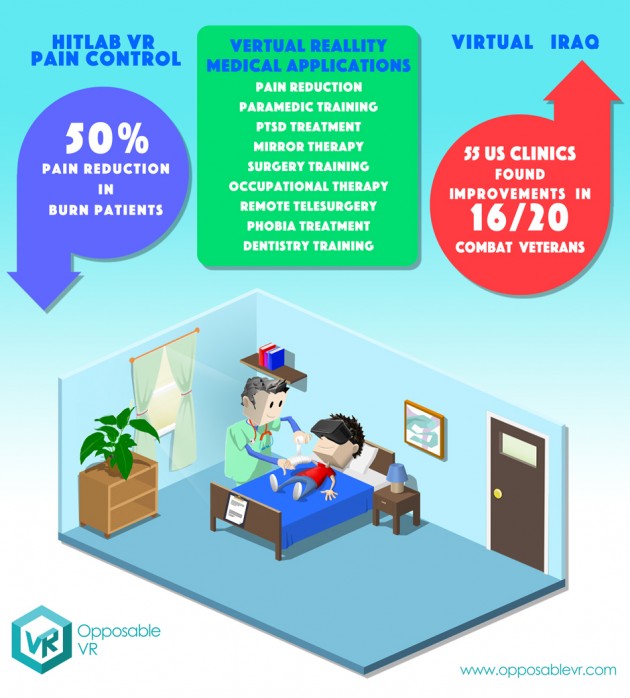

SnowWorld works on the basis that pain requires ‘conscious attention’ to be felt; VR, being about illusion and immersion, lures a patient’s conscious attention to stimuli in the VR world and away from the treatment they are receiving. In preliminary tests, HITLab found patients experienced a 50% reduction in pain felt and a marked drop in anxiety.

Pain and anxiety seem to be, currently, the most common applications for VR in medical therapy. One area in particular that has received much attention is in the treatment of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). The paper, Virtual Reality Applications to Address the Wounds of War, describes VR therapy as: ‘treatment typically [involving] the graded and repeated imaginal reliving and narrative recounting of the traumatic event within the therapeutic setting. This approach is believed to provide a low-threat context where the client can begin to confront and therapeutically process the emotions that are relevant to a traumatic event as well as decondition the learning cycle of the disorder via a habituation/extinction process.’Two such programmes at the University of Southern California’s Institute for Creative Technoloiges include Virtual Iraq – adopted by 55 veteran’s affairs clinics in the U.S. – and Bravemind, funded by the Office of Naval Research, which showed improvements in 16 out of 20 combat veterans.

Helping soldiers and combat veterans with Phantom Limb Syndrome (PLS) has also shown to be an area in which medical VR can leave its own mark. PLS is the sensation wherein an amputee can still feel their missing limb but are unable to see or control it, often resulting in a painful or distressing experience. A common form of treatment is ‘mirror therapy’ in which the patient looks at a mirror image of their missing limb, tricking the brain into syncing with the missing limb to reduce discomfort.

VR therapy, using electrodes attached to the patient’s missing limb, records muscle signals to control the movements of a virtual limb on the patient’s VR avatar. The patient can then control the virtual limb using their brain to complete tasks such as driving a car. According to biomedical engineers at Chalmers University of Technology, patients reported a reduction in phantom pain with some experiencing periods without pain at all during the therapy sessions. Engineers revealed that one of the biggest issues with phantom limb therapy is that patients don’t complete their therapy. It is hoped that VR will prove to be more fun and, therefore, engaging.

Being engaging is a key element of VR design. If the design and immersion fall out of sync then engagement is lost. Being able to engage with the experience is the foundation of a training programme created at the University of Texas, Dallas to help young adults with autism work on social skills. By creating virtual avatars of themselves, young adults with autism enter social situations such as dates and job interviews in order to work on identifying social cues and managing social expression. Initial tests showed VR to be a ‘visually stimulating approach to treatment’ with a noticeable increase in cognitive skills.

The audio-visual prowess of virtual reality is one of its strongest elements and, if used to full effect, can create a number of unique medical experiences. For people who are homebound or disabled, VR can allow them to step out of their homes or play the piano with their eyes. VR headset manufacturer Fove turned to crowdfunding to realise its Eye Play the Piano project. Fove’s chief executive believes that VR technology can ‘open up many new possibilities to all humans.’

As you may have noticed, however, all of the applications noted so far have been focused on therapy. Is there an application for VR in surgery beyond a training tool? There could be with a little help from our friend Augmented Reality (AR). It has been suggested that the future of surgery is ‘image guided’ in which preoperative data and the patient are merged into a single ‘scene’. The surgeon will see the pre-op data overlaid onto the patient’s body. We could certainly be some way off from such an application – and VR’s role in medicine still has some ways to go with many of the above experiences still in the testing phase, seeking approval from governing medical bodies - but it doesn’t hurt to imagine now, does it?